A Young Adult Reads “The Redeeming Mission of the Church.”

Redemptoris Missio, or redeeming mission, was promulgated in 1990 by St. Pope John Paul II to provide a new vision of mission for the church in an increasingly changing and pluralistic world. It remains the the most significant understanding of the Church’s understanding of global mission today. We asked Brian Ashmankas, a young man very active in social justice and peace to read Redemptoris Missio and provide his own take on it.

In 1990 when Pope John Paul II issued Redemptoris Missio, I was not yet four years old. I am a Millennial and the majority of my generation was not yet born. The formative events that shaped who we were, especially 9/11 and the Great Recession, were still far away. Now we’re all adults. Our cohort is wide and varied. It is impossible to generalize who we are and what we stand for, but because owe came of age amidst the same events and changes, many of us participate in the same trends and outlook. We are generally distrustful of institutions. This varies from skepticism of their efficacy to outright disdain depending on the person and the institution. We prefer movements to organizations and choose to be participants in various ways in various movements rather than members of a singular organization. These tendencies extend to our spirituality. Being spiritual but not religious is a very common identity among us. This often involves intentionally and consciously engaging in spiritual practices from a variety of religious and non-religious sources without being a member of any one religion and often while being skeptical of organized religion in general. Even as a practicing Catholic myself, I don’t see the need to limit myself to a single interpretation of the faith, often challenge the institution, and identify myself more as part of a Holy Spirit and Christ-led movement than a member of the Roman Catholic Church. Millennials frequently are also committed to various social justice causes, including combating climate change, dismantling institutional racism, challenging rape culture, and many others. However, at the same time the magnitude of these problems and their entrenchment often challenges our sense of hope. Often it is hard to imagine that the future will be better than today.

The opening paragraph of Redemptoris Missio offers a compelling counter to this sense of hopelessness in my generation. It recognizes the many challenges we face in the world, but describes them as evidence not of decline but of a mission far from completion. The mission of Christ the Redeemer is one always going forward regardless of how much it stalls from one era to the next. Millennials want to be part of movements and to be on the move. If a compelling case can be made to them that Christ’s mission in the world is the same as the work and change they wish to see in it, it would inject hope into my generation and encourage them to willingly join this movement.

I personally believe that Christ’s mission and the work of the Millennials frequently overlap in their scope. However, this case is far from a given. Some statements in this encyclical provide evidence for this. Other statements make such a potential harmony more difficult to realize. One of the latter is the dependent clause that is interjected into the powerful first sentence – “which is entrusted to the Church.” Skeptical of institutions and by claims of authority, especially monopolistic authority, Millennials will often be put off by such an assertion. Millennials will join movements that share the goals of Christ and his Gospel, but if the institution insists such efforts must go through it, such participation will be a non-starter. On the other hand, church need not be interpreted as an institution (although it frequently is). The originally Greek, ekklesia, refers to a gathering of those called out, a community on the move from one state to another. Furthermore, when I first read this statement I was not repelled but further attracted to the Church. A movement entrusted with the power and mission of Christ would be a valuable ally against the often insurmountable odds of overcoming violence and injustice. If it is endowed with this purpose from the divine, nothing can stop it from achieving its end. What a movement to take part in!

Unfortunately, its tendency to institutionalize, to self-preserve, and even to ally with the forces of injustice do slow down its mission and repel those who would otherwise participate in it. Frequently, this encyclical is bogged down by attachment to the first of these tendencies. It does, to its credit, seek to challenge and root out the latter two, but seems to not go far enough and even these recommendations do not seem to have been taken seriously over the past thirty years.

On the topic of institutions, John Paul II tends to entrust Christ mission to them. In section two, when he speaks of all Christians being part of the mission, he follows it immediately with a mention of diocese, parishes, institutions, and associations. This is echoed at the end of section three when the duty of believers is placed in the context of the duty of institutions of the Church and again when the task is assigned to be coordinated by bishops, four “societies,” and a dicastery. Millennials would not be surprised that little has happened in the past thirty years to implement the pope’s ambitious call for a renewal of a mission ad gentes. Our experience of institutions is that they are often stuck in their ways, embattled by in-fighting, and unwilling to take the risks necessary to succeed. If the pope had called for new movements, perhaps emerging out of, but ultimately unrestricted by, the existing institutions, perhaps such missionary enthusiasm as he called for would have been seen. There is precedent for this in the Church. The first beginnings of the Church were not an institution but a movement. Religious orders generally emerged out of movements led by a small group of people who attracted others, consider the Franciscans, the Dominicans, and the Jesuits to name a few. Sadly, in each case such movements tend to calcify into institutions over time as they seek to preserve themselves or otherwise drift away as quickly as they come. That is why the Church always needs more movements, inspired by movements of the Spirit, in every age, and needs to encourage rather than stifle these new movements.

Although his primary focus is on the work of institutions in this encyclical, John Paul II does bring forward some reference to movements in a few cases. The base communities from which liberation theology emerged (and which the encyclical makes a brief positive reference to in section 51) constitute a movement of a number of communities more than a formal institution. Section 37 references the young in particular. Like in other places, the emphasis is on “associations, institutions, special centers and groups, and cultural and social initiatives for young people,” once more assigning the task to institutions. However, this is followed by a call for the involvement of modern ecclesial movements. These are neither defined nor discussed further, but this provides an opening for my movement-focused generation to be involved and even to take the lead in this mission, if we are allowed to do so by the institutions and our elders who lead them. The future of the mission belongs to base communities and modern ecclesial movements, flexible, permeable with other movements, collaborative, and free to be courageous and prophetic.

John Paul II calls for the church to take “courageous and prophetic stands in the face of the corruption of political and economic power.” This is an area where Millennials are deeply involved and one which collaboration and participation with the Church is possible. The primary barrier to this is that the Church is also frequently the ally and even source of such corruption. The prophetic stands that the Church may take are often drowned in the consciousness of Millennials by its insistence on preserving its own political power and unjust disciplines. Authenticity is an essential value for most Millennials and a Church that courageously calls for justice on one hand, while maintaining and failing to call out its own internal injustices on the other, will keep most of my generation away from participating in its mission.

Redemptoris Missio does call for several actions that could remedy this problem. First is the already mentioned call for courageous and prophetic stands. More of these would draw Millennial participation, especially if such stands risk the Church’s self-preservation and are directed inward to its own institutions as much as outward. A Church that not only takes these stands but resources, encourages, and organizes others who take similar stands would find many new missionaries from the ranks of Millennials who wish to act for justice but often don’t know where to start or have the means of doing so. Surely the ability that religious life afforded young people to make a difference in the world was a large part of the surge in its participation in the first half of the twentieth century and such an opportunity can be again, especially if participation in the missionary work could be done through third orders that don’t necessitate a vow of celibacy.

Section 39 says that the church proposes, but never imposes. This is hardly an accurate assertion either historically or currently, however it does provide a helpful yardstick for a Church that wishes to reform itself into the authentic model that would draw Millennial participation. The document calls for the continual affirmation of peace, justice, brotherhood (sic), and concern for the needy (section 3), for the transformation of human relationships and the liberation from all forms of evil (section 15), and for authentic human development whereby people become more as well as have more (section 58). These are all considered important aspects of the mission and are all goals Millennials can get behind. They are ways to attract Millennials to believe and participate in the spiritual goals of the Church as well. However, this will only be successful if these goals are not tied to institutions, sought externally by proposal rather than imposition, and authentically applied internally.

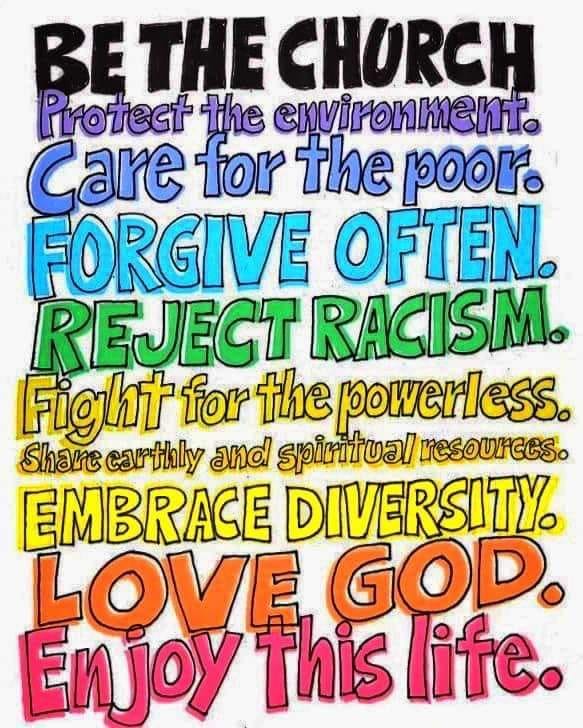

Section 86 reveals that John Paul II already saw the need for all of these even as he and the Church did not and still hasn’t fully embraced them. He saw a springtime for Christianity in the third Millennium as people everywhere were already in his time drawing closer and reaching a consensus on gospel ideals and values, among them human rights, nonviolence, justice, antiracism, feminism, freedom, and unity. We Millennials have embraced these values, but frequently without associating them with the Gospel or Christianity. We are concerned that many have begun to be curtailed in recent years rather than advanced. The Gospel and its values have outgrown the institution and inspired a wider movement. Too often the institution that has been their guardian works against this very movement, resisting the advancement of these values within its ranks and opposing their advancement in the wider world. Christ’s mission continues and has many willing missionaries among the most recent generation to come of age. They need only the hope the Gospel provides to prevent burnout and the spiritual and material support of those who shepherded the mission so far. Whether the Church will support that mission or resist it, whether it will advance the movement or preserve the current form of its institution remains to be seen.

Brian is from Auburn Massachusetts. His undergraduate studies are in Political Science. He was elected a Selectman for the town of Auburn. He worked on political campaigns at that time. He was an active member of Pax Christi Central Massachusetts,particularly with a Pax Christi unit that is in one of the State prisons. He was a member of the State Board of Pax Christi Massachusetts. He entered St. John’s Seminary in Boston for the Worcester Diocese where he was instrumental in starting a Pax Christi unit. He transferred to Theological College in Washington DC studying at Catholic University. He will receive his Master’s this Spring of 2020. He is now on the National Council of Pax Christi and serves as its treasurer.